Russian River History Part 2: From Fog to Sun

As we saw last time, the Russians ran into problems when they settled the far Sonoma Coast, on the beaches and benchlands near what is today called (in their honor) Fort Ross. In Russian River History Part 2, we’ll learn more about the challenges the Russians faced and their persistent efforts to try to keep their colony alive.

At first, things were pretty good. Their little colony flourished; a census in 1821 counted 175 adults, mostly men; only 24 were pure Russians, the others being Creoles, Aleuts, Pomos, Alaskan Chugash and other Native peoples. They planted the crops they needed to survive: wheat, apples, peaches, vegetables, and, of course, grapes for wine. They even tried to establish a beef and dairy industry.

Seaward View of Fort Ross

Image Courtesy, the Sonoma County Library

But what they didn’t count on was the climate. At Fort Ross the average high temperature in summer was only in the 50s. As for winters, the Russians were shocked by the fierceness of the storms that blew in from the sea, causing mudslides and rockslides that wiped out their farms and wooden houses. After some years, the Russians—having depleted their local supply of sea otters which they depended on for fur—had enough of the coast. They moved inland, to find a place to live that was “out of reach of the coast winds” (in the words of an 1885 newspaper article). They learned—as we very well know today—that the weather warms up and the fog burns off as you move east, away from the ocean.

The vines that wouldn’t ripen or got uprooted by mudslides must have particularly annoyed the Russians, who were hearty drinkers. They probably got their budwood—living splinters or sticks cut from existing vines, containing buds, used to plant vineyards—from somewhere to the south, possibly from the Mexican padres living along the coast, or even from as far away as Peru, as one 1817 account claims.

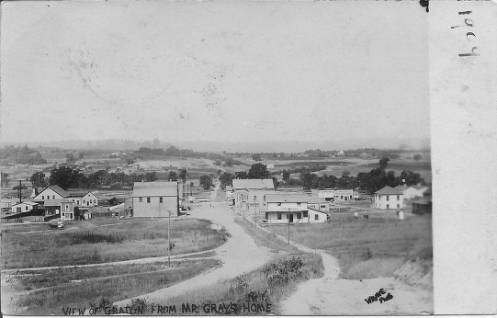

Wherever the Russians got their budwood, we do know that by 1836, they moved inland, and planted a vineyard in what is today the town of Graton, located within the boundaries of the Russian River Valley appellation.

Graton, 1909

Image Courtesy, the Western Sonoma County Historical Society

The man who planted the vineyard, Igor Chernykh, was quite a character: The Spanish, with whom the Russians got along just fine, called him “Don Jorge.” Chernykh was originally sent by the Russian government to help the hapless Fort Ross settlers, but even his extensive farming skills could not combat the awful weather. Chernykh, in a letter from 1837 to his superiors in Moscow stated, “About a dozen miles inland from Fort Ross, there are plains which are truly blessed…Fogs could not affect the crops there.” This is the area, around Graton, where the Russians moved.

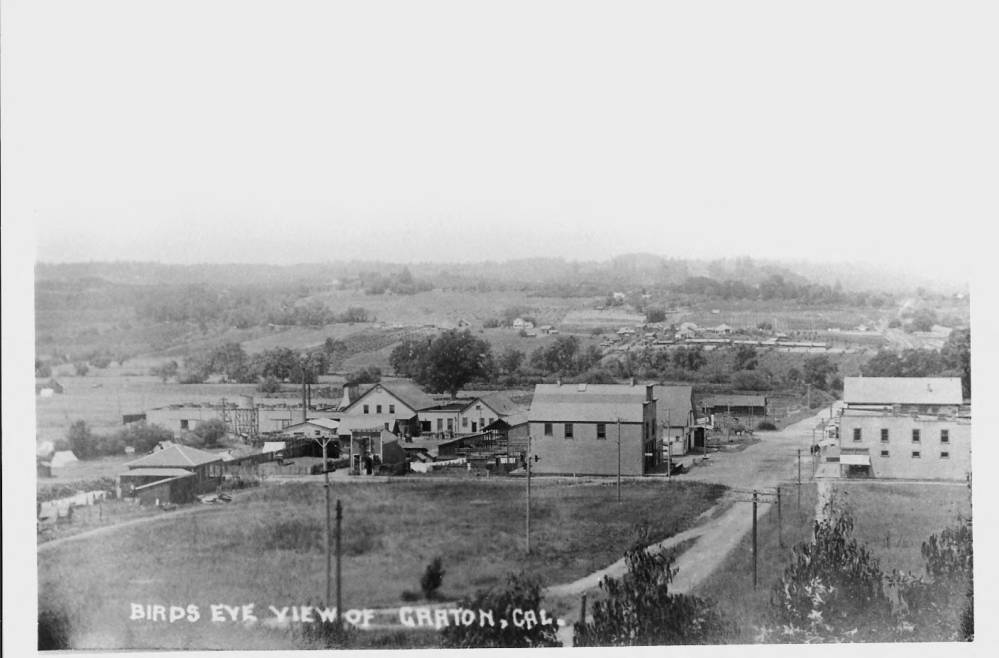

Birdseye View of Graton

Image Courtesy, the Western Sonoma County Historical Society

And yet, even in this sunnier part of Sonoma, they failed to thrive. Chernykh, in that letter to Moscow, complained the wine he was able to make from the grapes “does not keep well,” a real problem in those pre-refrigeration days. At the same time, American settlers from the east were pouring into the region, the immediate forebears of the Forty-Niners. The Mexicans too were pressing to extend their land claims northward.

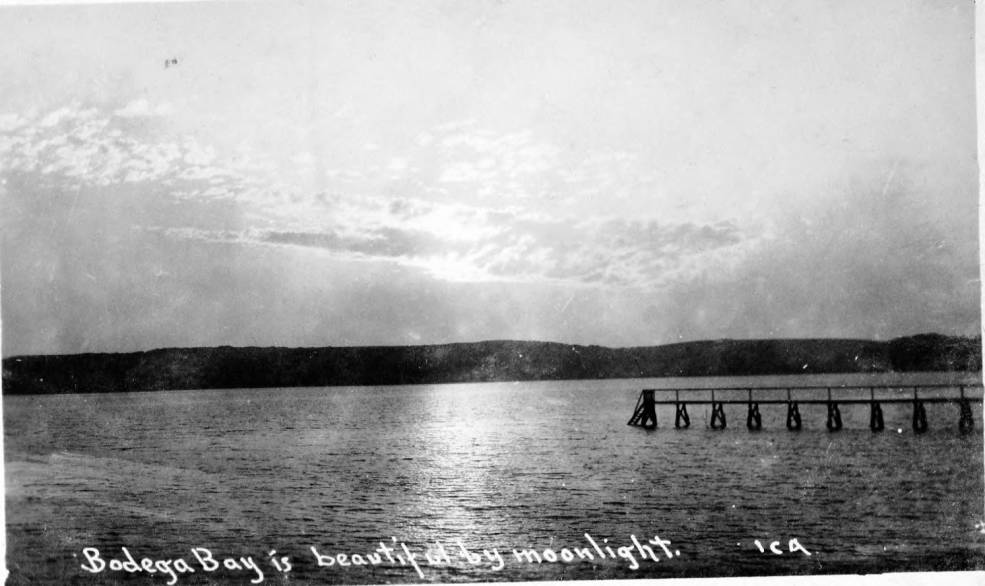

In 1839, the Russians, exhausted by 27 years of trying against all odds to keep their settlements alive, finally gave up. After some false starts, they finally sold their land to John Sutter. His 1849 discovery of gold at his Sierra Foothills lumber mill began the Gold Rush, which in turn brought tens of thousands of Americans into California. On New Year’s Day, 1842, the Russians sailed out of Bodega Bay, headed back to Alaska, which they still owned. They never did return to California.

Bodega Bay by Moonlight

Image Courtesy, the Western Sonoma County Historical Society

Next time, we’ll learn about the enormous influx of settlers, mainly of European extraction, that followed the Russian exodus, and set the stage for the Russian River Valley’s modern wine industry.

Russian River History Series:

Russian River History, Part 1: The Land Before Wine

Russian River History, Part 2: From Fog to Sun

Russian River History, Part 3: The Gold Rush to Prohibition

Russian River History, Part 4: From Prohibition to Modern Times

Comments