The Birthplace of Wine

When I first learned I’d be traveling to Tbilisi, Georgia for my brother-in-law’s wedding, I was a bit taken back. Georgia, which contains part of the Caucasus Mountains, is nestled in between the Black Sea, Armenia, Russia, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, and Turkey in an ancient land that has seen it’s fair share of conquests, occupations and wars. Once I started learning more about the Republic of Georgia, however, my fears settled quickly. Georgia and Armenia are both very safe and very friendly to foreign visitors, and are world renowned for their hospitality, and, of course, their wine!

Wine isn’t just a small part of the history of Georgia and the Caucasus Region—it is woven into Georgian and Armenian culture everywhere you look. In fact, upon landing in Tbilisi, one of the first things you’ll see is the Mother of Georgia statue standing tall above the city on a hill with a sword for her enemies in one hand, and a bowl of wine for guests in the other.

Mother of Georgia Statue, Tbilisi

The First Winemakers

Winemaking can be dated back to 8000 BC in Georgia, where evidence of grape cultivation has been found. Georgian museums house ancient wine-making pottery which dates back thousands of years. Many people think of Rome or Greece as the birthplace of wine, but the Caucasus region is where many experts believe the cultivation of grapes for wine was born. Some people believe the modern English name for wine is derived from Georgian Ghvino.

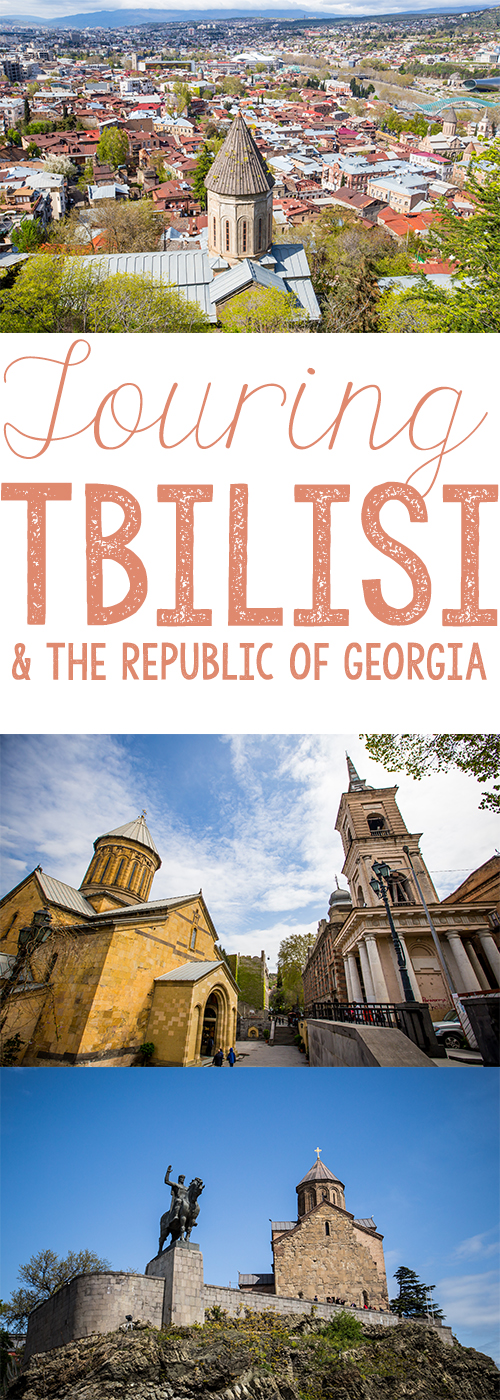

Tbilisi, Georgia

Georgia’s Capitol: Tbilisi

While the region had been considered unsafe for foreign travelers, The Republic of Georgia and Armenia are increasingly becoming safe and manageable for English-speaking travelers. Most employees in hospitality roles speak some English in Tbilisi and younger Georgians (especially in Tbilisi) also know English.

And thanks to a healthy exchange rate, Georgia is an incredibly affordable option for wine enthusiasts looking to experience a piece of history come to life.

The capitol city of Georgia, Tbilisi, can currently be reached by flights from Warsaw, Istanbul, Baku, and a few Ukranian and Russian cities.

Freedom Square, Tbilisi

Flying into Tbilisi is easy, but the airport does operate on a bit of an interesting timetable. Most flights arrive and depart in the very, very early morning. Our flight into Tbilisi from Istanbul landed at 3:00 a.m., and our flight out to Warsaw departed at 4:00 a.m. It is a strange experience to see so many people fully alert and buzzing around so early in the morning, but it is the everyday reality for a region that is still developing it’s appeal to international tourists.

While in Tbilisi, it’s easy to find hints of Georgia’s lengthy love affair with wine. Vines hang over alleyways and predominate people’s home gardens: A occurrence that becomes more-and-more evident as you move into the Georgian countryside.

Grapevines over cafes in Tbilisi, Georgia

Churches (which are more common than Starbucks in America), you’ll find patterns invoking grapevines, as well as the Cross of Saint Nino, all over elaborately painted and gilded décor. You can find ancient vessels used to hold wine in several museums in Tbilisi, and purchase homemade wine from roadside stands all around Georgia.

Exploring Georgia’s Connection to Wine

Though there was record of wine already being made in Georgia, the spread of wine throughout the Caucasus region as a vital addition to Georgian culture is widely credited to Georgia’s revered Saint Nino, whom many Georgians refer to as the “Patron Saint of Wine.”

Mtskheta, Georgia

We ventured north to the city of Mtskheta, one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world, dating back to 1000 BC. While visiting Mtskheta, tourists can trace Saint Nino’s steps at the confluence of the Aragvi and Kura rivers.

Tourists can visit to the Jvari Monastery which overlooks the ancient holy city and dates back to the 6th century, or to the Svetitskhoveli Cathedral which dates back to the 10th century and holds a number of historic artifacts as well as a very lively area with fantastic Georgian wines, liquors, crafts and delicacies for visitors. Both are UNESCO Heritage sites, and very worth visiting even for non-religious visitors.

Gates at Svetitskhoveli Cathedral, Georgia

Saint Ninos Cross, Sioni Cathedral, Tbilisi. The cross was made out of vines and is a crucial part of the history of wine in Georgia.

According to the church, Saint Nino came from Cappadocia holding a cross made from grapevines that she tied together with her hair and spread the use of wine as communion, as well as a social tradition. Her cross from grapevines was even used in baptisms—linking wine to Georgia’s history even more.

Sioni Cathedral in Old Town Tbilisi- where Saint Nino’s grape vine cross is held.

Today, the cross is held in the Patriarchal Sioni Cathedral in Tbilisi’s old town area, whose intricate décor holds lots of vine-inspired patterns and shapes.

Georgian Churches are often decorated with patterns and shapes resembling vines- as seen here at the Sioni Cathedral in Tbilisi.

Insider’s Tip: when visiting many Georgian Orthodox Churches and Monasteries, women must cover their heads, and sometimes wear skirts (the skirt rule is mostly just for monasteries). Most monasteries and churches have a basket in front where women can borrow an apron to tie around their waist if wearing pants, and borrow a scarf to toss over their heads. There will be signs marked, but it is easy to just follow what others are doing as not all churches require this. I simply tied a scarf to my camera bag so I could quickly toss a scarf on my head or sarong-style over my pants as I walked around the city.

Kakheti- Georgia’s Main Wine Region

Sunset on Sighnaghi

For visitors tracing interested in finding Georgia’s finest wines, the Kakheti region of Georgia is a must-see. Saint Nino, lived out her days and was buried at Bodbe Monastery- just outside the hilltop town of Signaghi, often thought of as the Sonoma County/Napa Valley of Georgia.

While our large group arranged for a tour bus, you can reach the Kakheti region by rental car (the road was in good shape and pretty easy to navigate, unlike some Georgian roads we saw). Or you can hire a driver for around 30 lari ($15), or take a marshrutka (bus) for about 5 lari ($2.50). Personally, I think a driver who speaks English is the way to go. They can help you find everywhere you’d like to see, and you’ll learn a lot about the history and culture of Georgia from them.

Saint Nino’s Monastery- Kakheti, Georgia. Saint Nino is often called the “Patron Saint of Wine”.

Once in Kakheti, you can still visit the Bodbe Monastery today and enjoy a glass of wine at a small café just outside the Monastery gates, while gazing out over the Caucasus Mountains that rise dramatically from the other side of the large Kakheti valley area, which is world-renowned for it’s winemaking.

Our group was treated to an intimate wedding reception (for my Brother and Sister in-law) hosted by the nuns. The food and wine were spectacular, and it was amazing to tour the lush and vibrant gardens that sprawl across the monastery grounds.

Vineyards at Bobde Monastery

After visiting Bodbe, it’s an easy trek to Signaghi (which literally means “shelter” in Azeri)- a spectacularly romantic town perched high on a hilltop, overlooking the Kakheti region and the Caucasus Mountains towards Russia.

Signaghi is a town composed of cobblestone streets, and dotted with small cafes, restaurants, boutique hotels, and wineries. It is a quiet, spotless, and gorgeous red-bricked display of history dating to the late 1700’s when it was used as a fortress from invaders.

Sighnaghi, Georgia

Now Sighnaghi is mostly known for wine, beautiful artisan carpets, and a booming tourism business that is friendly, affordable, easy for those who don’t speak Georgian, and quickly accessible from Tbilisi via a two hour drive or bus ride.

Just outside Sighnaghi, tourists looking for personal interactions with wine’s deep history in Georgia can find gorgeous vineyards that have been producing grapes for thousands of years- or get up close and see the ancient way of storing wine in large, earthen vessels called Kvevri, which are still used to age wine today.

Since ancient times, Georgians have added the juice of pressed grapes to Kvevri, which are laid into the ground and then sealed with beeswax and ash. Wineries aren’t the only Georgians to age their wine in potted vessels laid into the ground. Many homes have their own Marani (wine storage rooms) today.

Wine in Georgia can be a bit sweeter and less aggressive than American and French wines- but don’t let that steer you away! Most of the wines you can find in Georgia are organic- some even unfiltered- and tasting around is easy. There are officially over 400 varietals of Georgian wines- with 38 currently being produced by wineries (many other varietals are home-made, or have faded into history and aren’t favorites of Georgia’s active viticulture industry.)

As far as the varietals we drank in Georgia, one of my favorites was Kakheti Saperavi- a very dark bodied grape which makes for a rich, deep red color and bold, earthy flavors of black currant and toasted almond. I also adored Rkatsiteli- a white wine which looks like grape juice and smells sweet like honey- but surprises you with a very dry, full-bodied flavor of walnut and apricot. Georgian wines age well- especially those from Kakheti- and can be laid down for a few years if you can hold onto them that long.

We also found quite a few types of Khvanchkara- a full-bodied, semi-sweet red with notes of raspberry, blackberry, and pomegranate. Khvanchkara is rumored to be Stalin’s favorite wine, and is largely produced in Western Georgia and the regions around Stalin’s hometown.

There were a homemade wines I sampled that were very unlike anything I’ve had before- they are light red and have a thin mouthfeel, are sweeter and have notes of cherries and honey- and are incredibly drinkable. Many were not as alcoholic (one friend dubbed them “breakfast wine”) at about 6%, and made day-long supra toasting a bit easier.

Kvevri stored underground to age wine in a Kakheti area winery.

Winemaking in Georgia is not only intrinsically linked to the church, but the culture of Georgia as well. Literally everywhere you turn, you’re invited to share a glass and enjoy fabulous Georgian hospitality (and eat some of the best food ever- for more of what we ate in Georgia, head to this post on Sweet C’s Designs).

If you enjoyed learning a bit about the history of Georgian wine and places to tour the history of wine in Georgia, you need to check out this guide to throwing a traditional Georgian wine dinner- the Supra.

Supras are a spectacular show of hospitality and incredibly meaningful—as well as a lot of fun to be a part of. The entire meal revolves around a toast master, who guides the party through specific toasts, and keeps the meal full of fellowship. It’s a fantastic tradition we are dying to start up with friends here at home!

This is a sponsored conversation written by me on behalf of La Crema. The opinions and text are all mine.

Comments